The last month's been an odd one, as readers of this blog will probably have guessed; output here has dropped due to a combination of being busy and being ill, such that priorities haven't been what they were. My studies take most of my time, of course, and other matters have rode into second place, so the blog and other things have slipped a bit behind them. I'll be rectifying that from now on, all going well.

Work and other matters aside, I've not even managed any serious reading of late; Congar's The Meaning of Tradition remains unfinished and I've made little headway into David Copperfield. I have, however, managed to plough through Hergé's entire Tintin oeuvre, which has been both fascinating and fun.

There's an immense amount to say about Tintin, and no doubt pretty much all of it's been said already, but one of the first things that's struck me is how the boy reporter seems to be no more dedicated to his trade than Doctor Watson was to his practice or Father Brown to his parish. Indeed, were one to exclude the quasi-canonical Tintin in the Land of the Soviets and Tintin in the Congo from the Tintin canon -- as my set of hardback omnibus volumes does -- one would wonder about the veracity of Tintin's press credentials.

Tintin in the Land of the Soviets first began running in 1929, telling the story of how Tintin travelled to the infant Soviet Union in order to tell the world of the evils of communism; the story features the only instance in all twenty-four Tintin tales of the boy reporter actually filing copy.

Well, I say 'filing copy'; he writes a huge amount, but a whole series of shenanigans follow and there's no suggestion in the story that he ever gets around to filing his work; indeed, it seems to be left behind in his room as life gets in the way of his plans.

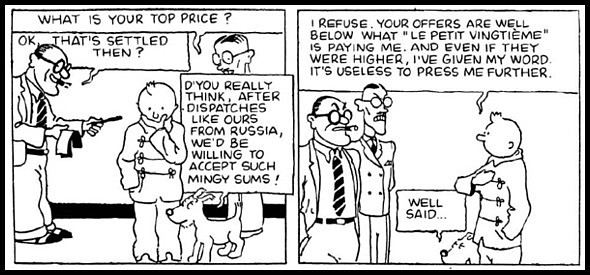

Still, he's evidently very successful, as Tintin in the Congo shows him being approached by several newspapers from other countries offering him huge sums of money to pay for his dispatches. Tintin, of course, will have none of this, having given his word to his own paper, Le Petit Vingtième.

This, as it happens, must have been a bit perplexing for those young readers of Le Petit Vingtième, a children's supplement, who surely wondered where Tintin's despatches were to be found. Search as they might through their weekly eight-page supplements, not once would they have found any of these dispatches for which Tintin was handsomely remunerated. It's all very fishy.

Making matters far worse is that we never again see Tintin doing even a jot of work. Sure, 1937's The Broken Ear features Tintin scribbling in his notebook while scurrying for facts, but even if we assume that he was in journalistic rather than detective mode at that point, it doesn't last long.

Making matters far worse is that we never again see Tintin doing even a jot of work. Sure, 1937's The Broken Ear features Tintin scribbling in his notebook while scurrying for facts, but even if we assume that he was in journalistic rather than detective mode at that point, it doesn't last long.

No, within a couple of panels he's chasing crooks, as is his wont, and he continues doing so, battling baddies and thwarting drug-smugglings and people traffickers for a further four decades or so, all the while being hailed as a great reporter whilst clearly living off Captain Haddock and coasting on his youthful reputation.

1 comment:

I was never convinced he was a 'boy' either. But his dispatches DID appear in Le Petit Vingtieme - just not in prose form...

Post a Comment